From the Telegraph:

Pensioners with care needs must stop regarding their homes as “an asset to give to their offspring”, the social care minister has said, as she revived the row over the Conservatives’ so-called “dementia tax”.

Jackie Doyle-Price said it was “unfair” for younger taxpayers to “prop up people to keep their property” when it could be sold to help pay for their own care needs.

I don’t read the Telegraph. I used to as a student but it’s not the newspaper it once was, and the rather hilarious adulation of Boris just makes it look silly. However someone commented on the above article on Facebook and brought it to my attention.

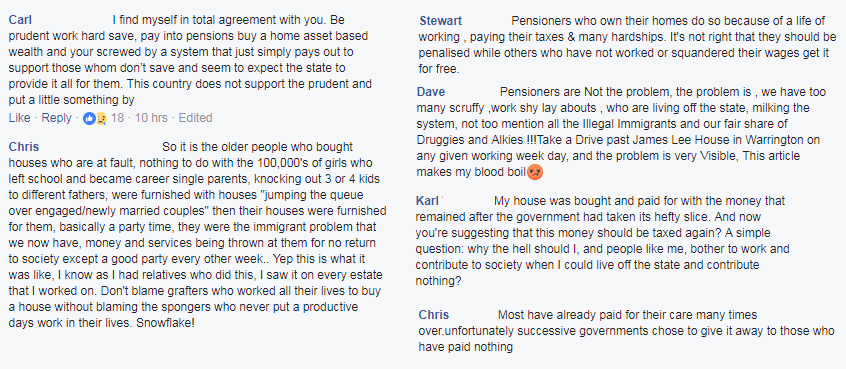

The comments were full of what I suspect are magenta hued baby boomers (closer to the 1946 vintage than the 1964 vintage mind), who were lambasting the government for penalising the hard working and frugality of their generation while allowing those spendthrifts in council homes to get away scot free. Their comments on the youth of today were equally scathing too. Here is a montage of invective, with surnames blanked out as I am nice like that:

There are the usual misconceptions to pick apart here, the most ingrained is probably the rose coloured spectacles that say the previous generation work hard in a way that the current don’t. Chris’ comments about girls chucking out three or four kids and hoovering up all the state money are typical of a generation that assume that because they grew up in a very special circumstance that has never really been repeated, their achievements are down to their hard work rather than circumstance.

What do I mean by this? Let’s time travel to 1966.

In 1966, an early baby boomer was 20 years old. The average wage in the UK was £891 a year. Tax was relatively high at that point; the basic rate on earnings over £300 a year was 42%. This meant an effective tax rate of about 28% for our average wage earner against about 12% now, once you factor in the tax free allowances. But there was no VAT in 1966, and the cost of living was low, as this article on Experian shows, which offsets the difference in tax rates and then some.

This generation also like to talk about the tax rate being in the 80%-90% when they were young too but that is again a huge red herring. A surtax was charged on unearned income (investment income for the most part) over a certain level, that brought the effective rate up to that horrendous headline figure but you needed to be earning many multiples of the national average wage to pay it. This was the tax regime that saw The Rolling Stones and many other rock stars leave the country. In other words, more tax was paid by those earning an awful lot of money.

Of course the biggest difference was house prices and their affordability.

In 1966 house deposits were typically 10% of the value and the average house price was £3,620. Today it’s 15-20% and a shade over £200,000 (or over £300,000 if you live in the South East).

This means back in the 1960s the average deposit was a little over a third of the average annual salary; today, with an average salary of £26,000, that deposit is over a year and a half of gross salary, which is four and a half as much as it was in the 60s.

And the cost of living is now higher.

Honest graft only gets you so far, and that’s something the older generation don’t fully seem to appreciate. While they were able to buy a house earning the average wage and see it appreciate over the last 50 years, someone on the average wage now simply cannot do that without significant help from their parents.

And that is the real issue with the so called dementia tax.

Anecdotally I know a lot of people who aren’t saving for their retirement, have large mortgages taken out until they’re 75, in the assumption that either they’ll inherit a valuable property that will pay for their retirement or that they will be able to downsize and live off the proceeds.

This approach of waiting for a windfall ignores several big issues though- firstly if care costs eat up inheritance, that inheritance may never materialise, and secondly, how exactly can you downsize and live off the proceeds if your children are still living with you because they cannot afford to buy a place of their own, and renting would remove any possibility of saving (rent takes an average of 48% of an under 30’s post tax income).

Comments from people like Karl also miss the point about tax and NI payments that they made. The common misnomer is that you pay your NI particularly into a pot that funds your pension. In reality what you pay is nominally used to pay the pensions of those already retired, and gives you an entitlement for a pension when you retire, that will be picked up by the tax payers at that time. In numbers terms, you always end up costing more than you’ve contributed. This is why the government is looking at a so called dementia tax to fund social care.

From my point of view I can see the argument for keeping homes with the family. I’d like to have a big wodge of cash at some point in the hopefully distant future that I’ve not earned but inherited but at the same time, I also think that I’m blowed if I should pay for the care for those that can afford it, just because they happen to have lived through a period of unrepeated prosperity, especially when there is a housing crisis on at the moment.